By David Stanczak

Much of the legal analysis in law school is taught via the hypothetical question, wherein the professor poses a set of facts embodying the issue studied, and asks students to predict the outcome, based on those facts. Although this is not a legal case, I pose the following business hypothetical:

The board of directors of the ILL Service Corporation has just named Jay Bee as its new CEO. Although new to the industry, Bee has a pleasant demeanor and looks to get along with the Board of Directors a lot better than his combative predecessor, Bryce Rambo. The new CEO knew when he applied for the job that the challenge would be daunting. The corporation is in a highly competitive industry. Business analysts have highlighted the corporation’s problems in a series of published studies which show that, while still a very large player in the industry, ILL has for several years been losing market share to its five nearest competitors, and this loss is accelerating.

While some of the company’s customers are on long-term service contracts, many, including most of its biggest customers, are not. This fact has been seized upon by its competitors, some of which are aggressively competing for ILL’s customers by reducing the price for their services. Customer satisfaction is also a problem. Many of ILL’s former customers, when questioned, replied that they switched due to dissatisfaction with the service they were getting for their money. The noted that better service had been promised the last time ILL raised its prices, but the promised improvements never materialized.

Bee believes in ILL’s potential. He is convinced that, if it can provide more services and a greater variety of them, the company can regain its dominance in the market. But the company is currently losing money, and the thought of expanding services seems out of the question without a massive infusion of cash. Because of the size of its short-term and especially its long-term debt, the company’s credit rating is awful, so a typical loan would come with a high interest rate, as would any bonds the company might issue, since they would be rated one level above junk.

Bee then seized upon the solution to the problem. The company’s services are more valuable to its more well-heeled customers. Therefore, they should be willing to pay more for them. The answer lies in a price restructuring. All new and renewal service contracts would be priced according to the customer’s income. Customers with incomes below a certain level would continue to pay for their services at the same price; those earning above that amount would have their price adjusted upward according to their income. Bee estimates that he can limit resistance to the price adjustment by limiting it to only the top 3% of the company’s customers; most customers wouldn’t feel a difference. Yet, despite their small numerical size, the richest 3% would pay enough additional money to allow ILL to expand the company’s service line, reduce the company’s debt, and improve the quality of the company’s services. Bee announces the restructured prices.

What result?

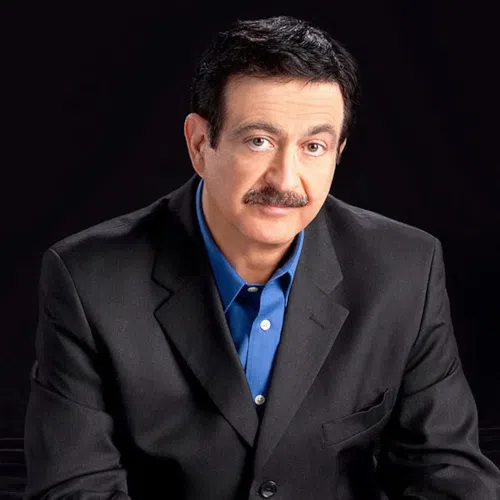

David Stanczak, a WJBC commentator since 1995, came to Bloomington in 1971. He served as the City of Bloomington’s first full-time legal counsel for over 18 years, before entering private practice. He is currently employed by the Snyder Companies and continues to reside in Bloomington with his family.

The opinions expressed within WJBC’s Voices are solely those of the Voices’ author, and are not necessarily those of WJBC or Cumulus Media, Inc.