By BETH HUNDSDORFER

Capitol News Illinois

[email protected]

SPRINGFIELD – The day before she was shot by a Sangamon County Sheriff’s deputy, Sonya Massey’s mother called 911 and said her daughter was in the front yard of her mother’s house, talking loudly, acting erratically with her car keys in her hand.

Afraid that she would drive recklessly and cause a crash, Donna Massey did what the counselors had told her to do. She called the police, even though she said she was afraid.

“I don’t want you guys to hurt her. Please,” Donna Massey said during a two-minute 911 call made the morning of July 5.

During that call, Donna Massey said her daughter was not a danger to herself or others but was having a mental breakdown and thought people were out to get her, like a “paranoid schizophrenic.”

Donna Massey made a request of the dispatcher.

“Please don’t send no combative policemen that are prejudiced. Please,” Donna Massey said. “They are scary. I’m scared of the police.”

The dispatcher reassured her that the officers would do their jobs.

“Help is on the way,” he said before ending the call.

Records show when law enforcement and medical personnel arrived, Sonya Massey refused medical care. She denied she was suicidal or homicidal. Records showed they left about an hour after getting Donna Massey’s call.

About 16 hours later, ambulance personnel would return to Massey’s residence, this time, summoned by deputies. Massey was lying on her kitchen floor bleeding from a fatal gunshot wound to her face.

Sean Grayson, was one of the Sangamon County Sheriff’s deputies that responded to Massey’s 911 call to report noises she had heard outside her residence near Springfield. Body camera video showed Grayson shoot Massey, who appeared confused during her exchange with the officers, shuffling through paperwork and looking at her cell phone. At one point, Grayson gives her permission to remove a pot with hot liquid from the stove. As she does, his partner moves back when Massey takes the pot.

“I rebuke you in the name of Jesus,” she said.

Grayson then threatens to shoot her in the face and puts his hand on his weapon. Massey ducks behind a counter, puts her hands up, apologizes then comes up and has the upended pot in her hand.

Seconds later, Grayson fires three times, striking Massey once just below her left eye.

After the shooting, Grayson radioed dispatch and asked whether Massey was 10-96 – police code for the mental health case.

Later, when a fellow deputy asked if he was all right, he responded, “Yeah, I’m ok. This f—ing b—h is crazy.”

At the scene, another unidentified deputy checked around the house prior to Massey being shot. Body camera footage showed broken windows on a car parked in Massey’s driveway.

In that body camera video, the deputies asked Massey who owned the car. Massey said it wasn’t hers and she said she needed help.

“Please, God. Please, God,” she said at one point during the exchange. “I don’t know what to do.”

Grayson asked if Massey was doing all right mentally.

“Yes,” she responds, telling officers she took her medicine. “I love y’all. Thank you, all.”

Grayson persists in his questioning regarding the damaged car.

Deputies enter the home and Grayson asks her name. Massey falters.

Massey tells the deputies she has paperwork to show them, but she can’t find it as she sifts through a bag on her couch. Sangamon County Emergency Telephone Systems Department/911 records show Massey had been in contact with mental health crisis teams after her mother’s 911 call the morning of July 5.

Massey had also called 911 the afternoon before she died to report that a neighbor threw a brick at her and broke the car windows.

Massey sounds agitated during the call, not speaking directly to the dispatcher. On the recording, she can be heard saying that she is looking for the neighbor.

“You come anywhere near this car I’m going to kill you, ho,” Massey is heard saying while on the 911 call.

Massey would offer police differing accounts, then agreed to go to St. John’s Hospital in Springfield around 2 p.m. on July 5, according to dispatch notes. She had abrasions to her arms and wanted treatment for her mental condition.

Dispatch notes show Massey would tell police at the hospital that she broke the windows herself so she could get inside her car. She said that she had been in contact with mobile crisis response teams earlier that week, and she believed the mobile crisis team and Springfield Police tried to run her off the road. She also said she had recently been discharged from a mental hospital in Granite City.

Gateway Regional Medical Center in Granite City operates a 20-bed, in-patient behavioral health unit. They did not return calls for comment.

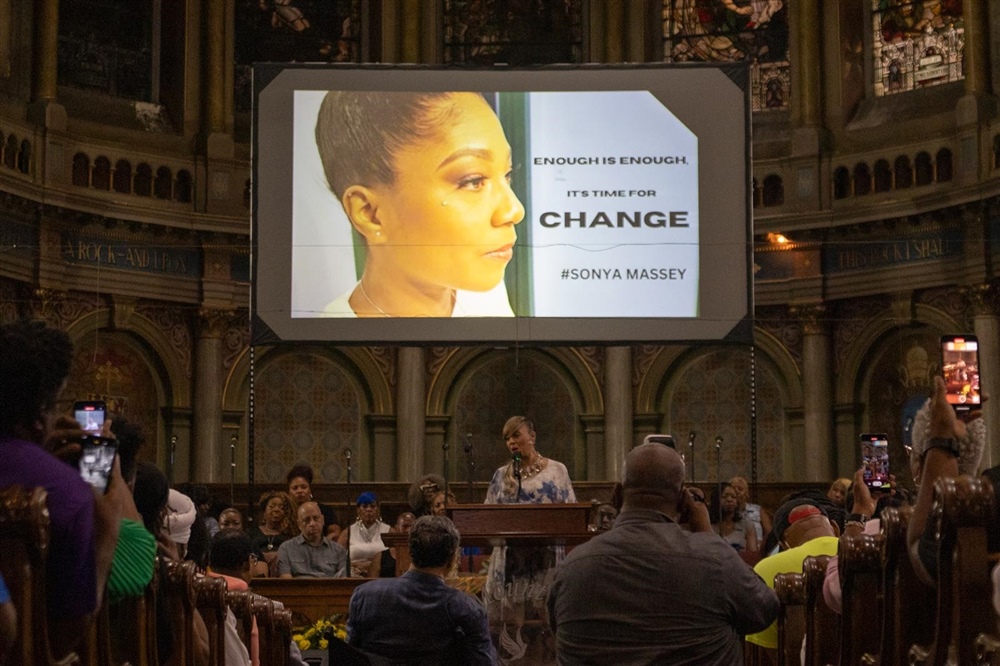

A Sangamon County grand jury indicted Grayson with first-degree murder in Massey’s shooting. He was fired from the sheriff’s department after the charges were filed.

The Illinois Fraternal Order of Police Labor Council filed a grievance last week related to Grayson’s dismissal, saying he was fired without just cause. The union was seeking Grayson’s reinstatement, backpay and lost benefits, but it dropped the grievance earlier this week.

Grayson, 30, remains detained until trial on the murder charges.

Grayson worked for six law enforcement entities in central Illinois in four years. Records showed that he was hired by multiple departments despite two driving under the influence convictions. The Logan County Sheriff’s Department also found that Grayson wasn’t accurate in his report writing and failed to halt a high-speed chase when his supervisor ordered him to terminate it.

Some of the concerns were documented in a two-hour meeting with Logan County Chief Deputy Nathan Miller. At the time of the meeting, Grayson was battling colon cancer and was working light duty.

Grayson resigned from Logan County in 2023 after he accepted a job at the Sangamon County Sheriff’s Office.

Capitol News Illinois is a nonprofit, nonpartisan news service covering state government. It is distributed to hundreds of newspapers, radio and TV stations statewide. It is funded primarily by the Illinois Press Foundation and the Robert R. McCormick Foundation, along with major contributions from the Illinois Broadcasters Foundation and Southern Illinois Editorial Association.