By HANNAH MEISEL

Capitol News Illinois

[email protected]

CHICAGO – It was a sunny and mild spring afternoon in May 2019 when roughly 100 FBI agents were dispatched to the homes – and one office – of eight allies to then-Illinois House Speaker Michael Madigan.

The coordinated raids – all conducted within the same hour or so to preserve “the element of surprise,” one of the agents told a federal jury on Monday – recovered documents and electronic devices from searches in Chicago, a near suburb and 200 miles southwest in Quincy, along the Mississippi River.

It was during the search on the home in Quincy, a custom-built ranch owned by longtime Springfield lobbyist Mike McClain, that agents found handwritten notes and email printouts prosecutors would later use to charge McClain and Madigan for running an alleged “criminal enterprise” for the benefit of those in the speaker’s inner circle.

The jury in the pair’s racketeering and bribery trial have already heard wiretapped calls and seen correspondence in which McClain described himself as Madigan’s “agent” and called the speaker his “real client.” Jurors have also heard several intercepted conversations where McClain joked that Madigan “thinks because I’m retired, I’ve got more time to do assignments,” as he told one colleague in early 2019. “Which is true.”

On Monday, the jury got the full picture of how McClain viewed his “assignments” from Madigan, with whom he’d been friends since the 1970s, when they’d been young Democratic legislators together in the Illinois House. Among the many items agents seized from McClain’s home on May 14, 2019, was a handwritten list recovered from a green tote bag monogrammed with McClain’s initials in the trunk of his Toyota Avalon.

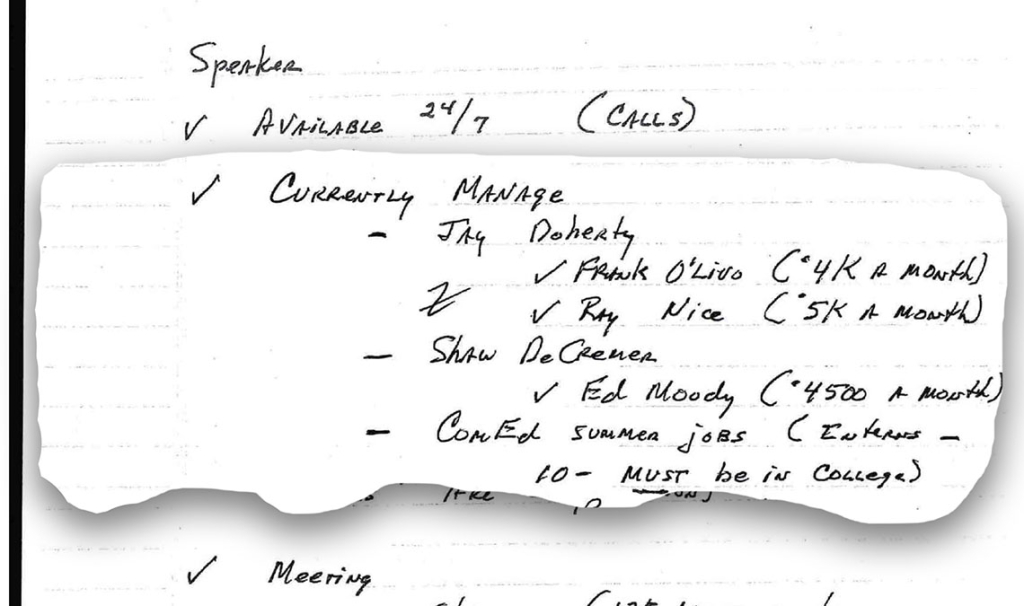

In a list spanning three pieces of yellow legal paper, McClain scrawled a list headed simply by the word “Speaker.” Leading the list, McClain wrote “available 24/7 (calls),” followed by a dozen other items denoted by checkmarks, most followed by a series of sub-bullet points further detailing the assignment.

Under one header labeled “diversion/saving Speaker and Mapes minutes,” McClain wrote “members/lobbyists seeking advice/wanting to visit with MJM/Mapes,” using the initials of Michael J. Madigan. Even after his official retirement from lobbying in late 2016, McClain could often be found in and around Madigan’s suite of offices in the Capitol in Springfield during lawmakers’ legislative session weeks.

And under another header, McClain laid out a list of Madigan allies who prosecutors allege were being indirectly paid by McClain’s longtime client Commonwealth Edison for little to no work. Between 2011 and 2019, five different Madigan allies were beneficiaries of these no-work contracts, worth anywhere from $4,000 to $5,000 per month.

The arrangement began with former Chicago Ald. Frank Olivo in 2011 and grew to include top precinct captains Raymond Nice and Ed Moody from Madigan’s 13th Ward power base on Chicago’s Southwest Side. Later, former state Rep. Eddie Acevedo and former Chicago Ald. Michael Zalewski would also get in on the deal.

ComEd indirectly paid out more than $1.3 million to the men over the eight years, payments that prosecutors allege were meant to bribe Madigan in exchange for favorable legislation in Springfield. The names on McClain’s yellow legal pad list indicate it was written soon after his retirement in December 2016 before Acevedo was added to the mix.

The Madigan allies were paid through trusted lobbyists, including longtime Madigan staffer Shaw Decremer, former Democratic state Rep. John Bradley and Democratic fundraiser Victor Reyes, whose law firm was also given a lucrative yearslong contract with ComEd after McClain’s intercession.

But no lobbyist had as many subcontractors or served as a conduit for as long as Jay Doherty, who was convicted along with McClain and two other former ComEd executives in a related trial last year.

The jury last week and Monday heard from FBI agents who searched Doherty’s downtown Chicago office and his home in a swanky condo in the affluent Streeterville neighborhood. Neither search turned up any evidence of work product put together by the subcontractors for ComEd, and Doherty’s former administrative assistant Janet Gallegos testified Monday that she was unaware of any work the subcontractors did for her boss.

But the agents did recover documents that indicated just how little the subcontractors spoke to the man whose name was on their checks. Olivo, the former alderman who’d been put under Doherty’s contract shortly after his retirement from city council in 2011, would usually write a little note to Gallegos on a fax cover sheet when he sent his $4,000 invoice each month. In two of the notes from 2013 and 2015, Olivo wrote “say hello to Jay.”

In a voicemail recovered from Doherty’s cell phone during the search of his home, McClain called to discuss how Moody’s subcontract might work after being appointed to the Cook County Board of Commissioners, an entity Doherty was registered to lobby on ComEd’s behalf. In it, McClain asked for Doherty’s permission to give Moody his cell phone number, despite the fact that Moody had been under Doherty’s contract for more than 2 ½ years at that point.

In a subsequent voicemail later that day, Moody called Doherty and gave him his cell phone number, saying “the Speaker wanted me to reach out to you.” Moody was then removed from Doherty’s contract and moved onto Decremer’s contract to avoid any conflicts of interest, ComEd executive-turned-FBI mole Fidel Marquez testified earlier in the trial.

The same day McClain wrote to Madigan announcing his retirement in early December 2016, McClain emailed Doherty to make sure Moody was paid for his last month, explaining in a follow-up message that the change in contracts was “a clean and definitive break” for Doherty.

McClain’s habit of printing out emails made the agents’ job a bit easier on May 14, 2019, as they searched his home office, another office area in the basement featuring a wall of filing cabinets and his car in the garage.

In one printout dated Dec. 9, 2018, agents found an email with the subject line “Magic Lobbyist List.”

“A Friend of ours and myself have gone through the ‘magic list’ and frankly culled quite a few names from the list,” McClain wrote to the bcc’d recipients of the email, employing his common euphemism of “our friend” when referring to Madigan.

McClain’s email continued with a request of those on the “magic list” – prominent Statehouse lobbyists, including some who’d spent years working in Madigan’s office and others who’d served in the General Assembly.

“So, I would ask what has been asked in the past,” McClain’s email continued. “If you have a potential client come up to you and seek you as a lobbyist but you cannot for whatever reason (accept the work) please engage him/her and try to get him or her to consider a recommendation from you.”

McClain closed by reminding the recipients that “a lot of ‘big issues’” would likely be up for consideration during the upcoming spring legislative session – Gov. JB Pritzker’s first in office.

The email, found in the same green monogrammed tote bag with McClain’s yellow legal pad list of “assignments,” appeared to be the explanation for several handwritten notes on stationary from the Talbott Hotel in Chicago’s Gold Coast neighborhood, also found in the bag.

The documents shown to the jury included several iterations of the same list of names. Some of the versions included a sort of rating system, with plus signs next to a few of the names. One also bore the speaker’s distinctive cursive script, adding names and phone numbers to the collection – and crossing one of his additions out.

As testimony wrapped on Monday, jurors saw a series of McClain’s calendar entries from the spring of 2019, revealing McClain had a meeting with Madigan one day before the FBI searches, and then had dinner with the speaker two days after the raids.

Capitol News Illinois is a nonprofit, nonpartisan news service that distributes state government coverage to hundreds of news outlets statewide. It is funded primarily by the Illinois Press Foundation and the Robert R. McCormick Foundation.